Thanks to Nason for creating a digital copy of the Fencing Tactical Wheel. A version in PDF format can be found via the link on the attachment page here.

-

Recent Posts

Categories

Thanks to Nason for creating a digital copy of the Fencing Tactical Wheel. A version in PDF format can be found via the link on the attachment page here.

French fencing masters wrote about the cavé (pronounced cahv-ay) as a distinct fencing action. In French, caver means to cave in or collapse. The cavé thus described how a fencer would change or position his wrist or body to create a sharp angle—“caving in” from, say, a straightened position—for a specific fencing purpose, whether offensive or defensive.

Sensibly, then, the cavé is sometimes referred to as angulation today. But that term doesn’t always cover all the ways the French writers used the cavé. This is because, as explained below, you can also cavé by using no angulation.

For the French, there were three ways to cavé. From the on-guard position, you could cavé (1) at the hips or (2) with your rear leg. You could also (3) cavé the wrist of your sword arm, which itself was possible in three different ways. These methods were variously defensive or offensive.

Importantly, these were not recommendations so much as taxonomy: as we’ll see, some of these ways of “cavé-ing” could get you killed.

1. The Cavé at the Hips

Danet discussed the “cavation” of the body in the second volume of L’Art des Armes. The cavé of the hips is one of two types of esquive—that is, a movement or displacement of the fencer’s target area to evade a thrust—that Danet identified. As Danet described it, the cavé at the hips occurs by “lowering the shoulders and completely straightening the right knee” (en baissant les épaules, & dépliant tout-à-fait le genou droit). (L’Art des Armes, vol. II, 127.)

Danet’s cavé at the hips is demonstrated below. For comparison purposes, Figure 1 below shows two fencers on guard. The cavé at the hips is at Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cavé at the Hips

In Figure 2, the fencer on the right has lunged, and the fencer on the left has performed the cavé at the hips, tilting his torso forward and straightening his lead leg to avoid being hit in the low line.

Danet disapproved of this sort of cavé. He believed it made a fencer neglect the parries, which provide more safety. Nonetheless, he did recognize that desperate times call for desperate measures, and, if you had to use it, the cavé at the hips avoided a low-line thrust—Danet gives the example of small-sword’s low quarte or quinte—by four or five inches.

Nonetheless, in my experience, caving in like this is hard to suppress: it is instinctual to retract at the hips when you perceive your opponent has deceived your attempted parry and is lunging under the hand. It takes time to suppress this instinct and to learn to rely on the parry or judiciously retreat (or both).

As mentioned, the cavé at the hips was one type of esquive. If you just had to defend without using your steel or footwork, Danet preferred the second type of equive. (Danet didn’t name this type, simply referring it to as the esquivement to distinguish it from the cavé.) To use this esquive when attacked, the defender straightened his lead leg and bent his rear leg “as much as possible” (le plus qu’il est possible), which pulled back his torso. (L’Art des Armes, vol. II, 134.) This pulled the defender’s torso back and away from the point, but he had to keep his lead foot on the ground to maintain his steadiness.

Figure 3 below shows Danet’s esquive. Notably, this esquive was also useful against high-line attacks. In fact, Figure 3 notwithstanding, Danet demonstrates the esquive against an attack to the inside-high line.

Still, there is some risk at using this esquive to the exclusion of a parry. Virtually all your weight is on that back foot. If the opponent quickly redoubles, then your cross-over retreat, accompanied by no parry, may not be sufficient to protect that open target you’ve provided.

By the 19th century, discussing the cavé of the body, whether for good or ill, seems to have diminished.

French writers also sometimes referred to the cavé of the rear leg. Used this way, cavé merely described extending the rear leg when you lunged. The leg “caved-in” from a bent position, maximally extending. For instance, when discussing the steps in the lunge, La Boëssière instructed his student to “cave in the left hip [with] the left foot perpendicular, and the hollow of the knee straightened” (cavez la hanche gauche, le pied gauche d’aplomb et le jarret tendu). (Traité de L’art des Armes, 74.)

Obviously, this is one of those instances when translating cavation as angulation doesn’t work.

By far, the French writers used the cavé to describe how a fencer bent his wrist, either on the attack or to defend. There are three ways to cavé with the wrist. You can cavé to (1) oppose, (2) go around, or (3) detach from the adverse blade. Let’s look at each of these.

This is the most familiar and proper use of the cavé at the wrist. You can do this when attacking or defending

Classical and historical fencers are taught to, when attacking, cavé the wrist—that is, angulate it—towards the opponent’s blade. This prevents the double touch, hinders the parry, helps keep the line open for attack, and angles the point towards the opponent’s body. Thrusting like this was known as thrusting “en cavant” (while angulating). See Figure 4 below.

You can see that, even if the defender were to thrust now, the angulation of the attacker’s wrist would deflect that thrust.

The cavé was also used as a distinct action against the flanconnade in which the opponent uses his blade to seize the weak of your blade, gliding along the length of your blade to land the hit.

Angelo’s The School of Arms was the first text to use the word cavé to describe a parry which opposes the flanconnade. For that reason, I have used two different illustrations from The School of Arms to illustrate how the cavé defends against the flanconnade.

First, Figure 5 shows Angelo’s demonstration of the flanconnade. Here, it looks like the attacker is just about to succeed.

Now, compare Figure 5 to Figure 6, another illustration from Angelo’s book, highlighting what the cavé looks like when used as a defense to the flanconnade. In Figure 6, the defender has used the cavé to deflect the attacker’s blade and is poised to riposte.

As Angelo explains it:

The reversing the edge from an inside to an outside, called cavé, is a parade where you must, with great swiftness, turn your inside edge to an outside, at the very time the adversary gains your feeble, by his binding, to direct his point in your flank, called flanconade [sic], you must form an angle from your wrist to your point, by which you will throw off the thrust, and the point of your sword will be in a line to the adversary. You must keep a straight arm, and maintain, with firmness, your blade, from fort to feeble.

(School of Arms, 30.)

(Besides the wrist, there may be another cavé at play here. Looking at some other on-guard positions in the book, it seem like the model here may have straightened the lead leg, which, as we just saw, was another way fencers defended with a cavé against a low-line thrust. But, as mentioned above, Angelo did not compare these two pictures in his text, so one can’t reliably juxtapose the first and second picture. Moreover, Angelo’s description does not refer to the lead leg. )

Thus, using the cavé against the attempted flanconnade realigns the blades in your favor: by moving your arm laterally to the outside, you place your blade’s strong against a weaker part of your opponent’s blade, nullifying his attempt to control your blade and giving you the advantage. (My experience has sometimes been that, Angelo notwithstanding, I have had to bend my elbow on the cavé, bringing my strong further down on my opponent’s blade to deflect it. I have found this necessary when my opponent had lunged deeply, whether from being too fast for my reaction time or simply not judging his measure correctly. Seconde seems to work best for this.)

This is the worst way to cavé with the wrist. Angulating the wrist to get around a defender’s blade deprives the attacker of opposition to protect him from the defender’s blade, as explained above.

La Boëssière called this a “grand défaut”—a huge mistake. As he defined it, to caver while thrusting is to “thrust without opposition in order to successfully touch the body with the point regardless of the parry” (tirer sans opposition pour faire gagner la pointe au corps indépendamment de la parade). (Traité de L’art des Armes, 20.)

In the 19th century, Grisier said that using the cavé at the wrist to go around the blade carried your hand “totally outside of the line and in the sense the most opposed to opposition.” (totalement hors de ligne et dans le sens le plus oppose à l’opposition). (Les Armes et Le Duel, 271.) He cautioned that it exposed too much of your target area to use it.

Danet observes that this sort of cavé is “always common with students due to their overzealousness to touch” ([t]oujours trop ordinaire aux Elèves par la trop grande ambition qu’ils ont de toucher). (L’Art des Armes, vol.II, 127.)

Figure 7 shows this cavé from above the attacker’s point of view.

As you can see, the attacker has sharply angulated his wrist to get his point around the defender’s blade, which is in quarte to close the inside-high line. And, but for the attacker’s cavé, the defender would have been safe.

But, due to the attacker’s imprudent cavé, they are now both in jeopardy. For reference purposes, figure 7 shows the cavé at completion: you can see that the defender’s point directly threatens the attacker. Thus, had the defender counter-attacked by merely extending her arm before the thrust arrived, she would have, due to her proper angulation, simultaneously parried the attacker’s thrust and landed the touch. Alternatively, she could thrust now and assure a mutual death.

In the past, writers recognized that some fencers deliberately snaked their point around your defending blade. In those instances, you were encouraged to deploy your off-hand to defend.

Against those who thrust with angulation [cavation] I oppose with the left hand and, at the same time, thrust with the right. If the caveur parries with his left hand, as is very likely, the student should be careful to elude the left-handed parry by, at that moment, beginning to pass his thrust over the hand. And if the caveur wants to deceive my student’s hand in the same way, the student should quickly make sure of his blade by circling around with his hand. . . .

Against those who thrust in angulation, you can parry with the steel. But I prefer parrying with the hand because it is the lot of the caveurs to profit from one parry separated by another, which certainly uncovers the body. . . .

A celui qui tire par cavation je fais opposer le main gauche, et tirer en même temps la droite; si le caveur vient à parer de la main, come cela est fort possible, l’Écolier doit avoir soin d’éluder sa parade de la main, en initiant dans ce moment repasser son coup au-dessus de la main; et si le caveur veut tromper la main de mon Écolier de la même façon, il doit tout de suite s’assurer de son Épée en recirculant avec la main . . . .

On peut à celui que cave parer avec le fer; mais je préfère la parade de la main, parce que c’est le sort des caveurs de profiter de la parade écartée de l’autre . . . .

Gerard Gordine, Principes et Quintessence des Armes (1754).

Finally, we have the use of the wrist cavé that is the opposite of angulation. This type of cavé describes how your arm’s bent position caves in to full extension to make a thrust. The most common example of this cavé thrust is the riposte after a prime parry. Anatomically, it is very difficult to maintain the prime parry’s angulation while extending to the riposte: quite naturally your arm goes from a bent position to a straightened one, detaching from your opponent’s blade. This transition from the bent, defensive arm to straight extension is the cavé in this instance.

In his The Theory of Fencing, Gomard specifically recognized the prime and quinte thrusts as cavé thrusts, i.e., “a thrust made by detaching from the line of opposition.”

Being thrust in cavé form, prime and quinte do not allow the fencer to protect himself with the blade. If he needs to, he can use his left hand, which he advances and places in front of his body . . . .

La prime et la quinte, qui se tirent en cavant, ne permettent pas au tireur de se couvrir avec l’épée; il peut, en cas de besoin, y supplér, qu’il avance et place devant son corps . . . .

(Théorie de L’Escrime, 145.)

On that point, we’ll end with a final quote from Gomard, who limited the use of prime and quinte because those thrusts did not allow for opposition (we’ve referred to this before).

In fencing, there is the principle that the fencer who attacks should be covered, that is to say, protected from the enemy steel’s reach in the line where the attacking fencer delivers the thrust. Because, among the eight bottes, prime and quinte do not allow opposition with the blade—in that you can only thrust them en cavant—it is necessary therefore for these two to break with the principle of opposition or to have resort to opposition with the left hand. . . . We have already said that the bottes of prime and quinte should not be used to attack, but only as a riposte or remise.

Il y dans l’escrime un principe qui veut que le tireur qui attaque soit couvert, c’est-à-dire garanti de toute attenite du fer ennemi dans la ligne où il porte de coup. Comme parmi les huit bottes, la prime et la quinte ne permettant pas l’opposition par le fer, puisqu’on ne peut les tirer qu’en cavant, il faut donc, pour elles deux, dèroger au principe de l’opposition, ou avoir recours à l’opposition de la main gauche. Nous avons déjà dit que les bottes de prime et de quinte ne doivent pas s’employer en attaque, mais seulement en riposte en remise.

(Théorie de L’Escrime, 288-89.)

Thanks to Michaela Yesis for demonstrating in the above photos. And, as always, thanks to Scott Wright for lending his photographic talents to Columbia Classical Fencing.

A pdf version of this document can be found here.

Domenico Angelo’s L’Ecole des Armes

Domenico Angelo posed for some of the plates included in his magnum opus, L’Ecole des Armes. Here he is demonstrating the first position of the salute [image cropped to figure].

L’Ecole des Armes would go on to be reprinted several times within the decade. Domenico’s son, Henry Angelo, edited and reprinted L’Ecole des Armes in an entirely English version, presented as The School of Fencing, in 1787. It is from J. Kirby’s 2005 reprinting of this version that Angelo’s commentary on choosing and mounting a blade is excerpted. Note: although I have replaced the medial “long-s” with the “standard s” for ease of reading, the remainder of the text conforms to Henry’s presentation of his father’s work in 1787, including the order in which the sections are printed.

The Method of Mounting a Sword.

You must observe not to file or diminish the tongue of the blade, for on that depends the stability and strength of your sword.

If the tongue is too big for the mounting, you should open the mounting; such as the gripe, shell and pummel, and tighten the tongue, by putting in splinters of wood, so as to render it firm. The pummel and button must be of two pieces; the button should be fastened with a hollow screw, four or five times on the tongue of the blade which is to be run through the pummel, and riveted according to the shape of the button, round or flat.

This is the best method of mounting a sword, and which I recommend to all swordsman. You will find this method very useful also for broad-swords, or half spadoons, commonly called cut and thrusts.

You must observe that the gripe of the sword be put on quite centrical to the heel of the fort of the blade, which should have a little bend above the fingers, when in hand, and let the whole mounting be turned a little inward, which will incline your point in carte. This way of mounting your sword will facilitate your disengagements, and give you an easy manner of executing your thrusts.

When one purchased a sword in the 18th Century, blade and hilt components were selected and assembled by a fourbisseur (furbisher). This plate, excerpted from Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedie article, Old Weapons, Plates vol. 4 (1765).

When purchasing a small sword in the 18th Century, one faced a multitude of options. Important considerations beyond preference for handling included style of hilt and blade, the fashion of the day, and one’s social status. The latter played an important factor as a sumptuary good and reflected one’s social class. One selected components for a customized weapon from a fourbisseur, or furbisher, who then assembled the weapon. Diderot and d’Alembert included a plate in their Encyclopédie illustrating exactly this cultural practice in the mid 18th Century. Angelo goes on to advise how to examine and select a blade.

How to Chuse a Blade, and its Proper Length.

I thought it necessary before I set down any rules for the use of the sword, two premise a few words not only how to mount a sword, but likewise upon the choice of the blade; for, with a bad sword in hand, bad consequences may ensue, be the person ever so courageous, and active. Some are for flat, others for hollow blades; whatever pains were taken with the former, I seldom ever found them light at the point; it is therefore difficult to render them light in hand; I would, never the less, recommend the use of them in battle, either horse or foot; but in a single combat, the hollow blade is preferable, because of its lightness, and ease in the handling.

A person should proportion his sword to his height and strength, and the longest sword ought not to exceed thirty-eight inches from pummel to point.

It is an error to think that the long sword hath the advantage; for if a determined adversary artfully gets the feeble of your blade, and closes it well, by advancing, it would be a difficult matter for him who has the long sword to disengage his point, without drawing in the arm, which motion, if well-timed, would give the other with the short sword an opportunity of taking advantage there of.

You should not fail observing, when you choose your blade, that there be no flaws in it; These flaws appear like black hollow spots, some long ways, others cross the blade; the first of these are frequently the cause of the blades breaking.

The temper of the blade is to be tried by bending it against anything, and it is a bad sign when the bending begins at the point; the good blade will generally form a half circle, to within a foot of the shell, and spring straight again; if it should remain in any degree bent, it is a sign the temper of the blade is too soft: but though it is a fault, these blades seldom break. Those which are stubborn in the bending or badly tempered, often break, and very easily.

Works Cited

Angelo, D. (1763). L’école Des Armes, Avec L’explication Générale Des Principales Attitudes Et Positions Concernant L’escrime. [with 47 Plates.]. R. & J. Dodsley: London.

Angelo, D., Angelo, H. (ed). (1787). The school of fencing: With a general explanation of the principal attitudes and positions peculiar to the art. By Mr. Angelo. London.

Angelo, D., & Kirby, J. (ed.) (2005). The school of fencing: With a general explanation of the principal attitudes and positions peculiar to the art. Greenhill Books: London.

“Fourbisseur,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 4 (plates). Paris, 1765.

Morgan, P. (2014). Personal Communication.

Not so easily found, this digitized plate from L’Abbat (Labat) is signficantly more detailed than the plates in the digitized treatise circulating the web. Note the defender’s bent blade tip. Monsieur Labat (the translator, Andrew Mahon, misspelled Labat’s name as L’Abbat) addresses this in his discussion in selecting a blade and hilt. He states in his section on “Of chusing and mounting a Blade” the following:

Some Men chuse strait Blades, others will have them bending a little upwards or downwards; some like them to bend a little in the Fort, and others in the Feeble, which is commonly called le Tour de Breteur, or the Bullie’s Blade. The Shell should be proportionable in Bigness to the Blade, and of a Metal that will resist a Point, and the Handle fitted to the Hand.

Excerpted from: The Art of Fencing; Or, The Use of the Small Sword by maître d’armes Labat. 1763. Andrew Mahon, Translator.

Full Text

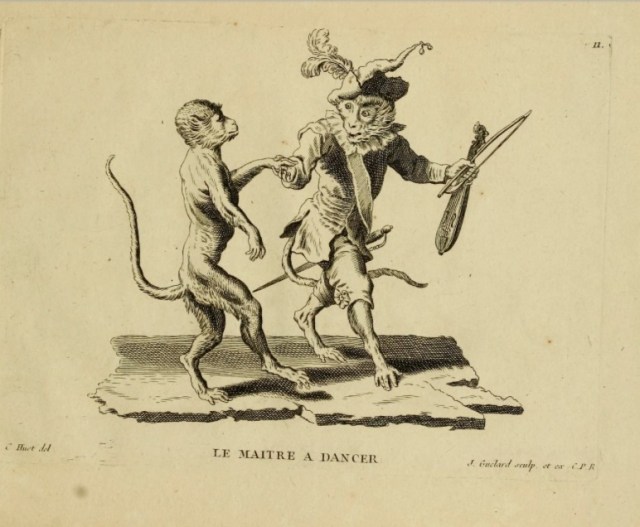

A gentleman of the 18th Century was schooled in the arts of fencing, dance, and horsemanship. What evidence do I cite? Well… the monkeys, of course!

The Fencing Master and The Dance Instructor

Christophe Hüet, from Singeries, ou différentes actions de la vie humaine représentées par des singes (Antics, or various actions of human life performed by monkeys), Paris, 1740.

Archive.org.